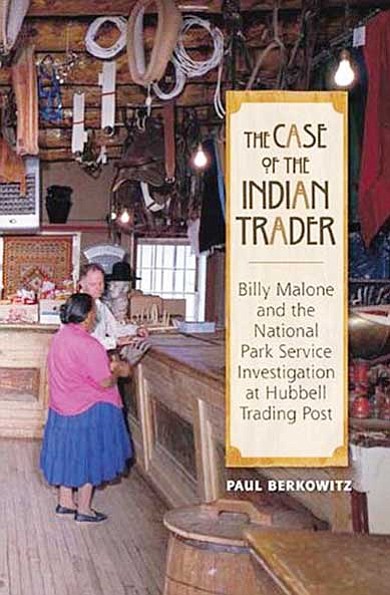

The Case of the Indian Trader: Billy Malone and the National Park Service Investigation at Hubbell Trading Post

Many older Americans became familiar with the National Park Service as children through the popular cartoon "Yogi Bear," chronicling the tale of a clever picnic-basket stealing bear versus a friendly if not distraught park ranger. Others have been fortunate to visit various national parks through family vacations, and have met helpful, friendly staff in person. As a whole, the National Park Service (NPS) is viewed with fondness and respect.

But like other federal agencies, it seems there is a darker side to the NPS.

In his capacity of a NPS special agent, Paul Berkowitz was responsible for investigating serious crimes committed in the national parks. He was asked to take over lead in the investigation of Billy Malone in late November of 2005.

"Berkowitz describes the culture of the agency and takes the reader through the history of how the NPS has evolved into an atypical bureaucracy, unique in all of government for both its idealistic mission and for the image it has cultivated with the American public. But that culture and public image has left the agency vulnerable to abuse by ambitious and unscrupulous employees, supervisors, and managers - including law enforcement personnel - whose own influence and raw political power has enabled them to operate with alarming levels of autonomy and freedom from meaningful oversight and accountability," writes Kevin Gilmartin, PhD, in the forward to The Case of the Indian Trader. (Gilmartin is a behavioral scientist specializing in police ethics and crisis management.)

Berkowitz lays out a carefully constructed and documented account revealing the mishandling of the Malone investigation at all levels - and evidence supporting his claim that his own supervisors and other senior officials in the NPS clearly wanted to see Malone arrested for anything in order to justify having spent two years and almost a million dollars in the investigation.

Berkowitz effectively describes the Indian Trader culture - how it began, how trading posts served Navajo communities, and the "special currency" that includes flexible and unconventional business practices necessary to conduct business in extremely isolated areas of the Navajo Nation. This currency included collectables like rugs, jewelry and other items. Traders did more than just buy or pawn hard goods; it was also common for the local trader - often an in-law - to assist customers with their correspondence, and to help endorse checks or to affix marks or thumbprints on other documents.

Berkowitz also examines the "partnership" between the National Park Service and the non-profit Western National Parks Association.

Billy Malone is described as one of the last of the authentic Indian Traders; a career that spanned almost 50 years. During that period, like many traders - or others who work on the reservation for that matter - Malone amassed a collection of Navajo arts and crafts. In the tradition of traders, Malone viewed such property as his life savings; safer and more dependable than banks.

Malone was the third genuine trader hired to run the trading post, and he was a natural and popular addition to the site, which he ran for 24 years.

Language from hearings before the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs established early in the 60s that the Hubbell Trading Post would be operated as a living trading post, and Public Law 89-148 (1965) authorized the NPS to purchase and establish Hubbell Trading Post NHS. The Hubbell family turned title to the NPS in 1967 with the binding stipulation that the site would be run as a "genuine working trading post."

"But in the decades that followed, Hubbell Trading Post evolved into a cash cow, the single most profitable site in the vast empire of nonprofit business operations run by the WNPA in more than sixty national parks throughout the West," Berkowitz writes.

With the turnover of administrative staff, unfamiliar with the business practices of a working Indian Trader - including a system of paperwork held in a shirt pocket or his own head - Malone's system set off alarms that precipitated a visit to the trading post in 2003. Fueled by conflicts with Jim Babbitt of the famous Babbitt Trading family, employee jealousy and conflict and Malone's practices that defied modern accounting programs, Malone was fired prior to a criminal investigation for a "forgery and embezzlement scheme" and his extensive personal property of rugs and jewelry was confiscated in a raid conducted on June 9, 2004.

Shockingly, Billy Malone had never been given the opportunity to tell his side of the story, and was not interviewed until after Berkowitz took over the investigation. That initial interview took place on Feb. 28, 2006, almost two years later, and led to Malone's cooperation in identifying confiscated property and other assistance.

What is clear from this account that had Berkowitz not become involved in the case, the outcome for Billy Malone would have been far different - but despite the U.S. Attorney's Office's decision to close its case file against Malone and not pursue prosecution, weighing Malone's personal suffering and the subsequent effects on his career and health as well as a lack of prosecution of other players, one is left wondering if true justice was had.

The Case of the Indian Trader is a fast-moving, well-written read.

SUBMIT FEEDBACK

Click Below to: