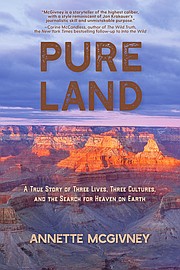

Book review: "Pure Land: A true story of three lives, three cultures and the search for Heaven on Earth"

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. —Annette McGivney’s new book “Pure Land” started with a story she wrote for Backpacker magazine in June 2007 about the murder of Tomomi Hanamure on her 18th birthday, May 8, 2006, by Randy Wescogame, a Hasvasupai tribal member.

In “Pure Land: A True Story of Three Lives, Three Cultures and the Search for Heaven on Earth,” McGivney does not shy away from the stark facts of the most brutal murder in Grand Canyon history.

But to tell of Hanamure’s life and death, McGivney also tells Wescogame’s story — one of domestic violence, which, in the course of researching and writing the story, McGivney discovered was her own story, too. She also tells a story about Native American genocide and historical trauma and its effects on not just the Supai people but Native American tribes across the nation.

It is those details that elevate Pure Land from its origins when McGivney first wrote about it for Backpacker magazine and make the book worth reading, not only for those who have traveled to Havasupai to see the waterfalls, but also for people who wonder why the Supai are largely confined to the bottom of the canyon — when the Grand Canyon had been their home for hundreds of years.

It would have been easy to write about Wescogame as a foreign person who was hard to understand. He did murder Hanamure by stabbing her 29 times, not something everyone can relate to. There was no reason to write about him as a complete, complicated person with a history that while not an excuse for the eventual murder, is an explanation for how Wescogame could have been brought to the point where he met Hanamure on the trail and decided the course of his life and the end of hers.

That the reader can come away from the book feeling empathy for Wescogame is entirely because of McGivney’s unflinching ability to look at her own past and describe her own experience with domestic violence at the same time that she tells of the abuse in Wescogame’s past.

“I’m not wanting to minimize in any way what Randy did,” McGivney said. “But it is not as simple as just saying he was mentally ill or a sociopath.”

McGivney said that one of the main things she wanted to get across in Pure Land is that everyone is connected despite living in a world where people are divided by culture or religion and child abuse can happen anywhere and its effect is far reaching.

“I guess I wanted to break down those barriers and show that it’s not that simple,” McGivney said.

The original Backpacker story garnered many comments with people sharing their experiences hiking down into Supai and recording what they saw there — with typical responses of how beautiful the area was while also commenting on the conditions they saw around them, but with no real thought to the Supai people and their history.

But what the Backpacker story lacked in giving that detail and history about Supai, McGivney makes up for in “Pure Land.” As a pure history lesson of colonization and its effect on indigenous populations, especially the Lakota and the Supai, “Pure Land” shows the continued effect of that colonization that the United States has never fully taken responsibility for.

“One of the big things I wanted to get across in this book is, I feel European immigrants are partly responsible for what could have maybe led to the murder because of what it did to the Havasupai culture,” McGivney said.

Still, McGivney realizes that no matter how full the history she gives or how compassionately she writes, there are still Supai people who may not want to revisit this particular moment in history — they still may want to push the murder under the rug, as they did when it happened and keep denying Wescogame’s existence.

But there is rich Supai history here that McGivney tells with help from the special collections section at Cline Library, which may be the only place some of the history is recorded. That Wescogame’s great, great grandfather was Billy Burro, the Indian at Indian Garden in the Grand Canyon. The oppressive history parks and monuments have had on Native tribes by curtailing their freedom and shrinking their homelands.

“People view Grand Canyon National Park as just this amazing place but it was very oppressive to the Havasupai,” McGivney said. “The way the park treated the Havasupai, the fact that the trails everyone hikes on, all the infrastructure was built with the blood and sweat of the Havasupai.”

McGivney said knowing that history can make trips to Havasupai more meaningful.

“I would hope that this ultimately helps Havasupai tourism,” McGivney said. “But that people go in there with a more honest view… we know what the challenges are here, so we’re not going to be put off by trash because we understand now. And we understand why there is not an ATM down here. I would like the tourists to be more compassionate instead of going down there with a customer view. I did try to honor [the Supai] but not to minimize the problems and not to absolve the Supai of all responsibility either.”

Hanamure is not alone in her fascination with Native American culture. In many ways it mirrors the stereotypical views of many others, some of whom are those hikers who want to see the falls in Supai.

But in researching and following Hanamure’s path as she visited the United States time and time again, McGivney shows Hanamure’s interest went more than skin deep.

Hanamure was drawn to places like Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation, not a typical tourist spot, but a meaningful one to Native American people. She stayed for three weeks, in the winter, on Pine Ridge. She stayed at a Hogan on the Navajo Reservation, becoming friends with the woman who let her stay there and learned how to weave a Navajo basket. She adopted a Pine Ridge reservation dog, Blues, a 90-pound mongrel and brought him home to Japan with her.

“She was really committed to the pure part of Native American culture,” McGivney said. “And it’s there. It’s too bad that it is embroiled also in all the current survival issues in modern American capitalism. She was really invested in learning more about things that were the authentic American experience. Indigenous cultures are at the root of that.”

The sad irony is it was that love that brought her face to face with Wescogame May 8, 2006. In that moment, Hanamure is living what she has been searching for for years — how to respect Native people. She recognizes Wescogame and tells him that she respects him moments before he kills her. That moment is documented in his confession.

It is a sad moving moment.

McGivney gives a lot more of those moments in the book, some her own, some Hanamure’s, some Wescogame’s and some of the Supai and Native people as she traces Hanamure’s life and death. She takes the reader on a journey through little known areas, onto Native American reservations, and to Japan. She takes people into the heart of domestic violence and how three people’s lives had three different outcomes because of it.

It is a moving journey and a journey worth taking.

SUBMIT FEEDBACK

Click Below to: